Welcome to DU!

The truly grassroots left-of-center political community where regular people, not algorithms, drive the discussions and set the standards.

Join the community:

Create a free account

Support DU (and get rid of ads!):

Become a Star Member

Latest Breaking News

Editorials & Other Articles

General Discussion

The DU Lounge

All Forums

Issue Forums

Culture Forums

Alliance Forums

Region Forums

Support Forums

Help & Search

Editorials & Other Articles

Showing Original Post only (View all)Monstrification [View all]

For centuries we’ve used the declaration of ‘monster’ to eject individuals and groups from being respected as fully human

https://aeon.co/essays/those-declared-monsters-are-ejected-from-the-human-family

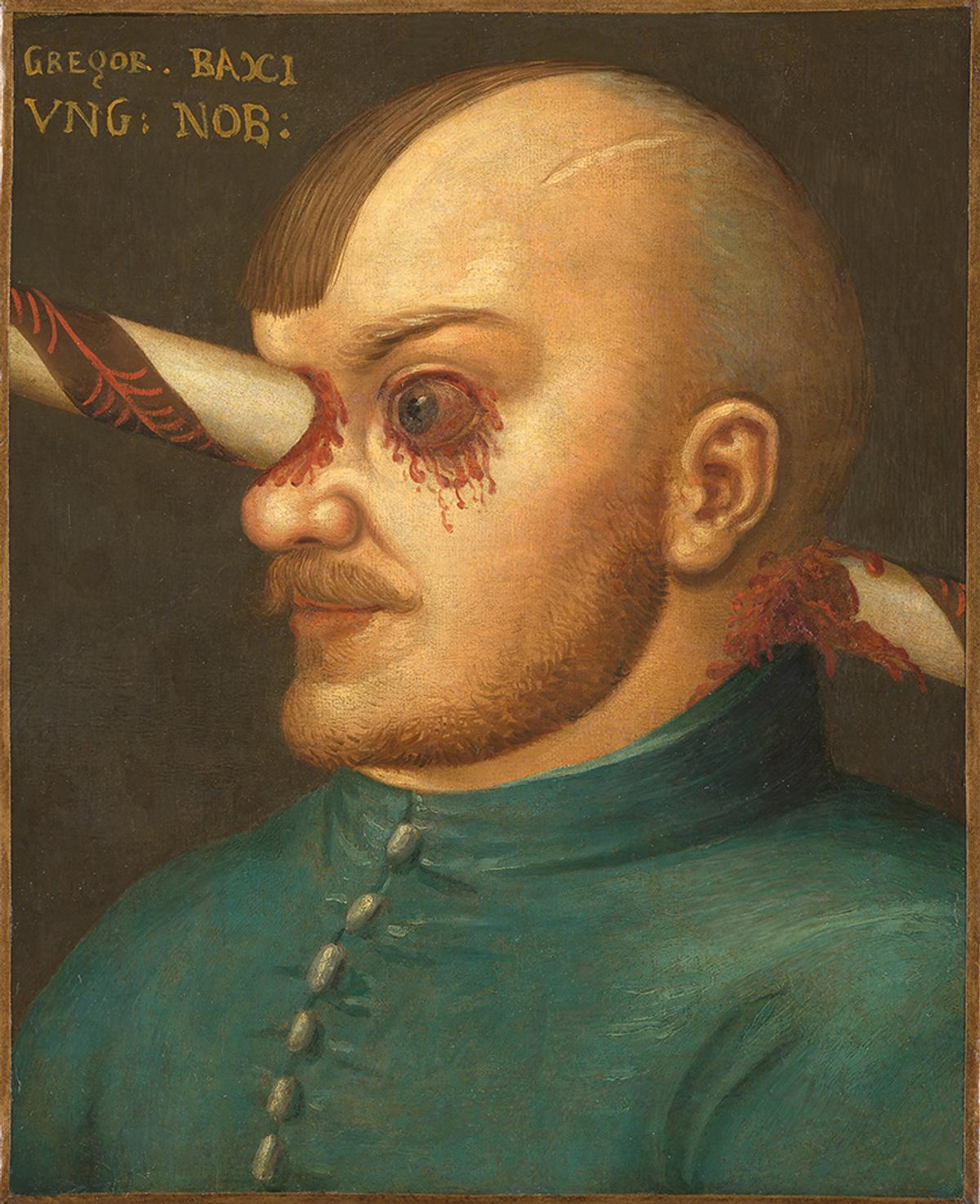

Portrait of Gregor Baci (16th century) by an anonymous German painter. Courtesy Schloss Ambras, Innsbruck.

At the edge of the town of Innsbruck in Austria perches Schloss Ambras, a Renaissance palace with a medieval core. Now a museum complex with gardens patrolled by peacocks, it contains a large room stuffed with what 16th-century visitors called wonders and curiosities. On the wall, a row of portraits depicts various people: a giant; two dwarves; a person with congenital joint problems; a man gored through the eye with a lance; Vlad III, known as Țepeș or the Impaler (the 15th-century ruler of Wallachia, in present-day Romania, who inspired Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel Dracula); and four members of the Gonsalvus family, whose father Petrus and multiple children were so hairy that some were given as gifts from one aristocratic household to the next and pawed over by physicians for ‘science’.

The Giant Anton Frank (Franck) with the Dwarf Thomele (after 1583), attributed to an anonymous German artist. Courtesy Schloss Ambras

Vlad III (16th century), attributed to an anonymous German artist. Courtesy Schloss Ambras

Portrait of a Disabled Man (16th century), attributed to an anonymous German artist. Courtesy Schloss Ambras

For 16th-century artists, physicians, naturalists and collectors, these atypically embodied individuals represented people beyond the edge of ‘normal’. Individuals with unusual physiques or lifestyles were routinely featured in collections, artworks and manuscripts devoted to what were then known as monsters. Libraries in the 16th and 17th century contained books like Ambroise Paré’s Des monstres et prodiges (1573) and Ulisse Aldrovandi’s Monstrorum historia (1642), in which numerous human beings appear.

Petrus Gonsalvus, born 1556 (1580), attributed to an anonymous German artist. Courtesy Schloss Ambras

Madeleine Gonsalvus, daughter of Petrus Gonsalvus, born 1574 (c1580), attributed to an anonymous German artist. Courtesy Schloss Ambras

Enrico Gonsalvus, son of Petrus Gonsalvus, born 1576 (c1580), attributed to an anonymous German artist. Courtesy Schloss Ambras

There’s a long Western tradition of identifying beings as monsters. In many cases, it’s clear why: basilisks or dragons are monstrous, as are more humanoid forms like zombies, vampires and werewolves. Monsters are categorically different from garden-variety creatures and typically, but not necessarily, fictional and alarming. But telling stories about monsters isn’t simply a way of describing beings that are nothing like humans. It’s also how societies define and police who they think counts as fully human, through acts of what I call monster-making or monstrification. Monster-making doesn’t always require the label ‘monster’, nor does it require defining a person as part-animal or supernatural. I see monstrification as any attempt to convey that an individual or group has broken the category of a ‘normal’ human being, via their bodies, minds or culture.

History shows that there has long been a blurry, moving line between the categories of human being and monster. This line threads its way through the people whose portraits appear in an uncanny corner of the Schloss Ambras curiosity cabinet, and continues into the present day, often justifying discrimination and other harms against individuals and groups who differ from a majority. It is also an ever-changing boundary, as social, political and technological developments alter its shape and position, and open up new forms of monstrification. Some of the most heated debates of our age – from trans rights to immigration reform to the ethics of AI – are underpinned by ancient fears of monstrosity, and cynical attempts to exploit them. And, in turn, today’s monster-making will shape the future, by redrawing the experience (or absence) of human rights, the horizons of possibility to live freely in safety and dignity, and the laws and systems under which people live. So, where does the human end and the monster begin? The boundaries are more porous than we might like to think.

snip

2 replies

= new reply since forum marked as read

Highlight:

NoneDon't highlight anything

5 newestHighlight 5 most recent replies

= new reply since forum marked as read

Highlight:

NoneDon't highlight anything

5 newestHighlight 5 most recent replies