Monstrification

For centuries we’ve used the declaration of ‘monster’ to eject individuals and groups from being respected as fully human

https://aeon.co/essays/those-declared-monsters-are-ejected-from-the-human-family

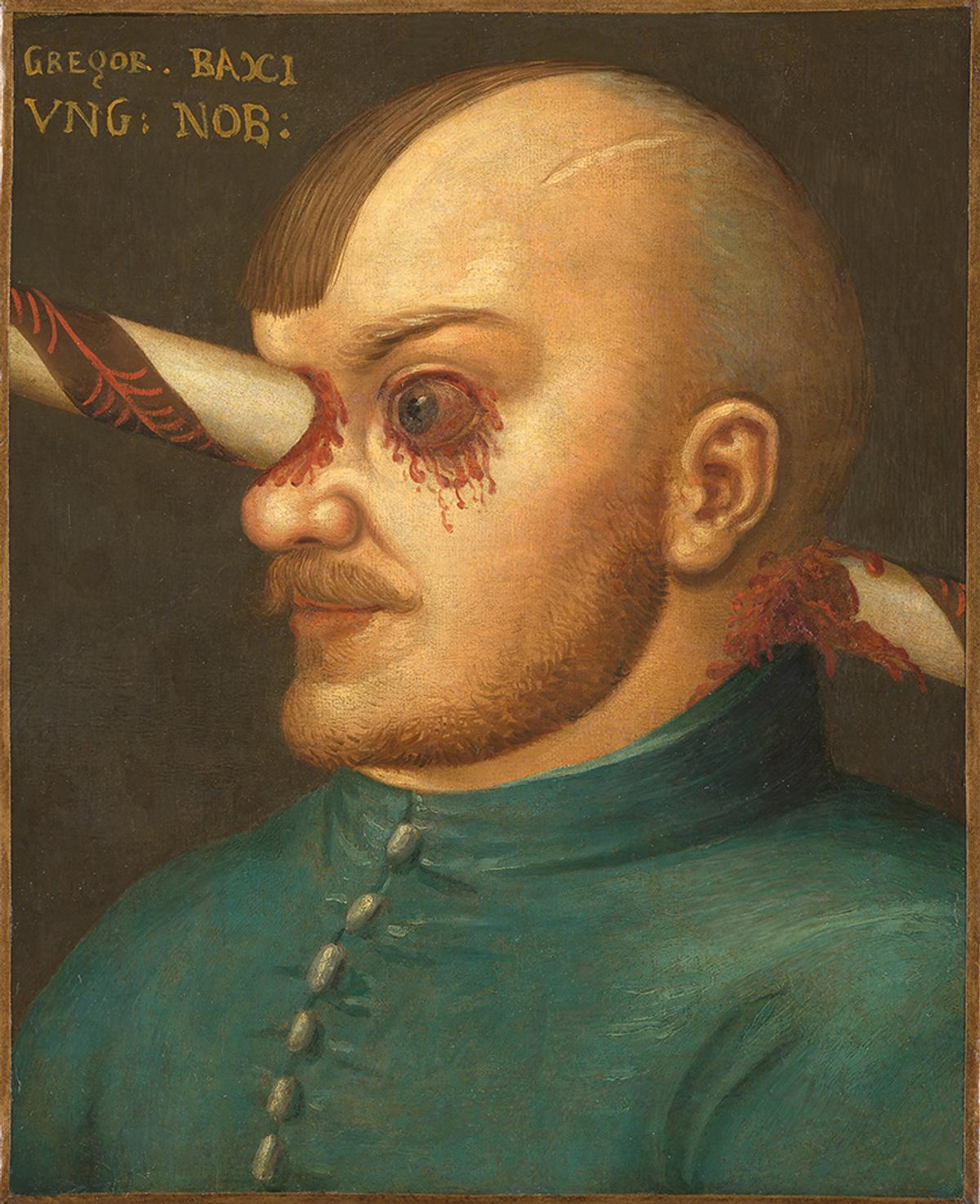

Portrait of Gregor Baci (16th century) by an anonymous German painter. Courtesy Schloss Ambras, Innsbruck.

At the edge of the town of Innsbruck in Austria perches Schloss Ambras, a Renaissance palace with a medieval core. Now a museum complex with gardens patrolled by peacocks, it contains a large room stuffed with what 16th-century visitors called wonders and curiosities. On the wall, a row of portraits depicts various people: a giant; two dwarves; a person with congenital joint problems; a man gored through the eye with a lance; Vlad III, known as Țepeș or the Impaler (the 15th-century ruler of Wallachia, in present-day Romania, who inspired Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel Dracula); and four members of the Gonsalvus family, whose father Petrus and multiple children were so hairy that some were given as gifts from one aristocratic household to the next and pawed over by physicians for ‘science’.

The Giant Anton Frank (Franck) with the Dwarf Thomele (after 1583), attributed to an anonymous German artist. Courtesy Schloss Ambras

Vlad III (16th century), attributed to an anonymous German artist. Courtesy Schloss Ambras

Portrait of a Disabled Man (16th century), attributed to an anonymous German artist. Courtesy Schloss Ambras

For 16th-century artists, physicians, naturalists and collectors, these atypically embodied individuals represented people beyond the edge of ‘normal’. Individuals with unusual physiques or lifestyles were routinely featured in collections, artworks and manuscripts devoted to what were then known as monsters. Libraries in the 16th and 17th century contained books like Ambroise Paré’s Des monstres et prodiges (1573) and Ulisse Aldrovandi’s Monstrorum historia (1642), in which numerous human beings appear.

Petrus Gonsalvus, born 1556 (1580), attributed to an anonymous German artist. Courtesy Schloss Ambras

Madeleine Gonsalvus, daughter of Petrus Gonsalvus, born 1574 (c1580), attributed to an anonymous German artist. Courtesy Schloss Ambras

Enrico Gonsalvus, son of Petrus Gonsalvus, born 1576 (c1580), attributed to an anonymous German artist. Courtesy Schloss Ambras

There’s a long Western tradition of identifying beings as monsters. In many cases, it’s clear why: basilisks or dragons are monstrous, as are more humanoid forms like zombies, vampires and werewolves. Monsters are categorically different from garden-variety creatures and typically, but not necessarily, fictional and alarming. But telling stories about monsters isn’t simply a way of describing beings that are nothing like humans. It’s also how societies define and police who they think counts as fully human, through acts of what I call monster-making or monstrification. Monster-making doesn’t always require the label ‘monster’, nor does it require defining a person as part-animal or supernatural. I see monstrification as any attempt to convey that an individual or group has broken the category of a ‘normal’ human being, via their bodies, minds or culture.

History shows that there has long been a blurry, moving line between the categories of human being and monster. This line threads its way through the people whose portraits appear in an uncanny corner of the Schloss Ambras curiosity cabinet, and continues into the present day, often justifying discrimination and other harms against individuals and groups who differ from a majority. It is also an ever-changing boundary, as social, political and technological developments alter its shape and position, and open up new forms of monstrification. Some of the most heated debates of our age – from trans rights to immigration reform to the ethics of AI – are underpinned by ancient fears of monstrosity, and cynical attempts to exploit them. And, in turn, today’s monster-making will shape the future, by redrawing the experience (or absence) of human rights, the horizons of possibility to live freely in safety and dignity, and the laws and systems under which people live. So, where does the human end and the monster begin? The boundaries are more porous than we might like to think.

snip

milestogo

(22,161 posts)One was about a child born with 2 heads to a poor family in the Amazon. They could not be separated. The weaker one died and his brother died - they were aged 6 months. The family was very loving and they did end up with a lot of high end medical support. But the mother had never had an ultrasound for this child or any of her other pregnancies.

The other was about a girl born with no face. Her face lacked bone structure and the features she did have were out of place. She also had a lot of high end medical care, including 25 surgeries by the age of 5. She was able to go to school.

In an earlier time these babies would have been considered monsters and allowed to die. There are many such people living among us but its still difficult for them to appear in public.

PoindexterOglethorpe

(28,272 posts)documentaries?